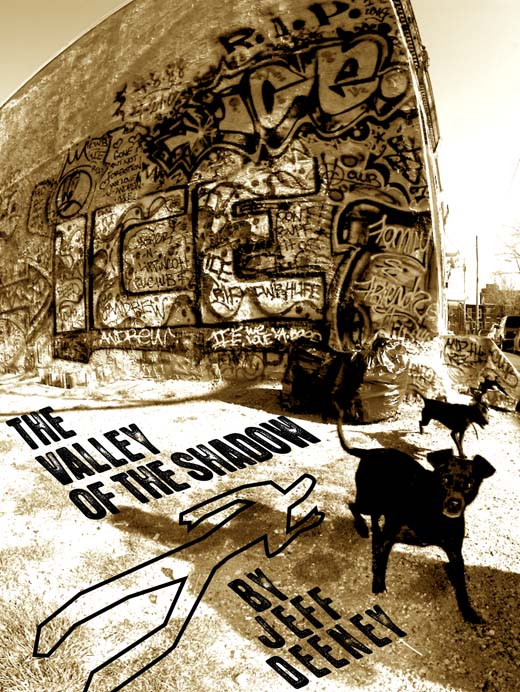

The Valley of the Shadow is was an ongoing series documenting how those in Philadelphia’s poorest and most violent neighborhoods publicly mourn and commemorate their dead. Jeff Deeney, the man who brought you Today I Saw, knows these neighborhoods well from his days as a social worker. The hope is was to shine a light on the city’s untouchables, brighten the darkest corners and gather-and-share ultra-vivid and all-too-real stories of loss, grief and remembrance.

BY JEFF DEENEY Initially the Valley of the Shadow series was conceived as a documentary effort aimed at exploring the street memorial phenomenon that has become such a prominent part of life in the city’s poorest and most violent neighborhoods. As a social worker doing heavily community based field work early this year I was seeing big, colorful piles of stuffed animals near the scenes of recent homicides on an almost daily basis. These public mourning displays were visually arresting; one of the regular criticisms I heard while writing the Today I Saw column back in 2007 was that it could have been strengthened by a photo component. I connected with photographer Justin Roman, who was willing to ride along with me into the neighborhoods, and the series was underway.

BY JEFF DEENEY Initially the Valley of the Shadow series was conceived as a documentary effort aimed at exploring the street memorial phenomenon that has become such a prominent part of life in the city’s poorest and most violent neighborhoods. As a social worker doing heavily community based field work early this year I was seeing big, colorful piles of stuffed animals near the scenes of recent homicides on an almost daily basis. These public mourning displays were visually arresting; one of the regular criticisms I heard while writing the Today I Saw column back in 2007 was that it could have been strengthened by a photo component. I connected with photographer Justin Roman, who was willing to ride along with me into the neighborhoods, and the series was underway.

Upon closer inspection it became clear that most of the memorials and their surroundings were covered in coded information like abbreviated corner crew names and street aliases for the deceased’s associates. I knew from observing my client’s children during social work home visits that kids in the neighborhoods are obsessed with Myspace. Plugging these bits of coded information into Myspace yielded a startling amount of often incriminating information; hundreds of young Philly kids were online showing off their gun collections, drug stashes and money stacks. The new objective for the series became to combine this previously unavailable intelligence with research from source materials like newspaper stories and court documents and my own knowledge of Philly’s neighborhoods based on my social work experience to create a more sociologically rich crime reporting than what’s in your daily newspaper.

[Photos by JUSTIN ROMAN]

The results were fascinating, though they received a wildly mixed reception depending on the audience. The fact is that most Philadelphia murder victims aren’t entirely innocent. Many of the victims whose memorials I wrote about were, judging by the extent of their criminal histories — and often according to their own webpages — street soldiers who died in the line of fire. When I encountered such victims, I portrayed them in the series as they portrayed themselves online. Friends began to write in, saying it was disrespectful to post pictures of the deceased posing with guns and money stacks even though these pictures were posted publicly online, often in a celebratory fashion, by the victim or his associates. Some neighbors pulled me aside when I was in the community to tell me that they knew the victim and felt that he was a bad person who terrorized the neighborhood. The same victim’s family and friends would attest to what a positive figure he was, a good kid who got mixed up with the wrong crowd. Behind each memorial was a complicated story, and telling it without stepping on any toes had become essentially impossible.Sometimes, like in the case of the a Erie Avenue Mob’s Tim “Boosa” Haines, these debates over the victim’s character eventually spilled from the streets into Phawker’s comment section. The pushback against the disrespect perceived by some readers who personally knew Haines intensified, and soon enough I was getting a fairly steady stream of threats from members of the Erie Avenue Mob. I started getting ominous messages from the friends of other victims I had written about. By mid-summer it was starting to feel like the project had gone completely haywire, and that increasingly large swaths of the city were becoming potentially dangerous territory for me to be in. This was especially problematic as I work in the same neighborhoods I write about and usually don’t have a choice about where I’m going to be working on any given day.

I sought out some expert advice, turning to Dan Rubin at the Inquirer, asking what he would do in this situation. Not surprisingly, in his long career as a journalist he’d been in similar situations. His advice was to pull the plug. I had made my point and the diminishing returns of continuing the column were becoming outstripped by the risks of writing it. Honestly, it was the answer I was hoping to hear. The column wasn’t so important that it was worth getting shot at, which is where it appeared to be heading. It was time to put the Valley of the Shadow to rest.

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: 22nd & Dauphin

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: 31st & Berks

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: 52nd & Larchwood

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: There Will Be Bloods

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: East Germantown

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: Lippincott Street

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: Westminster Ave.

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: 54th & Kingsessing

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: Cecil B. Moore Avenue

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: 11th & Tioga

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: Second & Glenwood

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: Amber & Cambria

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW: 55th & Sickels